2010 - Galleria Gagliardi, Milano

Luca Beatrice

Luca Beatrice

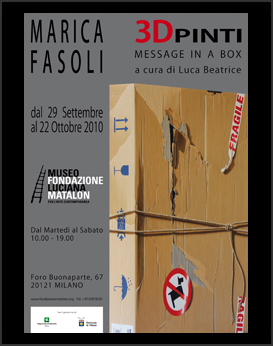

MESSAGE IN A BOX

But in actual fact, what was happening, among so many difficulties and uncertainties, was that, having abolished depth, the sense had shifted to inhabit the surface of evidence and of things. It didn’t disappear, it shifted. The reinvention of superficiality as a place of sense is one of the feats that we’ve achieved: a work of spiritual craftsmanship that goes down in history.

Alessandro Baricco, The New Barbarians

Art and craft have always walked hand in hand. The principle of making things, the manual skill inherent in the creative act, has distinguished the great masters throughout history. However, calling upon craftsmen, like paid workers to put the idea into practice, was the most revolutionary act within the world of conceptual art that moved the focus from the object to the idea. And here the masters come back into play: from Marcel Duchamp to Donald Judd, from Jeff Koons to Damien Hirst. The artist, along with them, has become the holder of the idea and not necessarily of its implementation; others are responsible for the task of conveying practical form to it, as though in any kind of industrial process. It happens in design and architecture, and it has happened in art, weakening the concept of “original” work.

On the strength of this assumption, Andy Warhol set up his art Factory in 1964. The most irreverent action, among the many exhibited by the Pop Art genius, was to dismiss the value of the work as an act of aesthetic mimesis. The subjects of his works become those common to the consumer society - coke bottles, fridges, boxes, supermarket objects – and nothing else. His perfect “copies” of Campbell’s Soups and Brillo Boxes require a semantic shift of the educated spectator from the content to the container. No commercial manufacturer claims brand originality which is perfectly identical to a product already on the market. “But who before the pop artist would have thought to make sculptures out of grocery boxes?”1

Warhol’s Brillos go beyond the ready-made style of Duchamp: his are perfectly made copies – in wood – painted and silkscreened “three-dimensional photographs of the original products”, where even the “imperfections” are part of the environment, identical to an industrial procedure. Not revision but mechanical reproduction. It is no longer the object but the process that is ready-made.

“Given two objects that look exactly alike, how is it possible for one of them to be a work of art and the other just an ordinary object?”2; attention has to be shifted to the action and not the result. In other words, it is the result that conveys sense to the aesthetic fracture: an everyday item, its apparent surface, its brand, its ordinariness is the only voluntary reason for introducing it, with an act of historic violence, to the harem of artistic production.

“Andy, your art could not be described as original sculpture. Would you agree with that?”

“Yes”

“Why do you agree?”

“Well, because it’s not original.”

“You have just then copied a common item?”

“Yes”3

(1 - 2 – 3 Arthur C. Danto, Andy Warhol, Yale University Press, 2009)

Does painting simulate reality, or is it reality that simulates the pictorial action? It’s hard to identify the limit between the subject and the method used to portray it. Especially when painting is contaminated to such a point where it’s impossible to perceptively differentiate between illusion and reality. Boasting an excellent manual skill which requires no assistance, the young Marica Fasoli has set up her own self-managed Factory. A mixture of Pop Art and Hyperrealism, of all-round painting and object minimalism. In her works she uses recognisable objects – corrugated card used in packaging and its content, whether this be real or imitation – to interpret the deceit of art.

The concept of mimesis – or imitation – introduced by Plato as the foundation for classic aesthetics, is made redundant. The ultimate aim of art is to reveal its essence. Little does it matter whether the bicycles inside those boxes are skilfully painted or physical inserts of mass products decontextualized. As sustained by the American critic and philosopher Arthur Danto, looking at the experience of Pop Art and the conceptual art of the Sixties and Seventies, the nature of the portrayal comes to itself.

While in the States Warhol presented the Brillo boxes, in Europe the standard idea of painting was being completely overturned. The tools used to make art were stripped of their functionality, not exhibited but induced by a paradoxical gesture. Shortly afterwards, Giulio Paolini, in Italy, showed reversed frames, white canvases, brushes laid in the corner of rooms. The surface reflects on the sense and it’s not the mere support of representation.

It is the progressive shift of the limit of portraying reality, having reached its highest level of description, reiterates the illusion, the platonic “copy of the copy”, to a purely conceptual fact.

In Marica Fasoli’s painting, the deceit of reproduction is the dramaturgy of appearances staged on the surface of the canvas. The object within it is confused by a super-illusionist technique which finds its pictorial matrices in the American Hyperrealism of Richard Estes, Chuck Close and the more recent Anthony Brunelli and Robert Gniewek. Without any 3D special effects, these artists anticipated the compartmentalisation of the image brought by digital technology by about twenty years. In this way Marica Fasoli explores the possibilities of hyperrealism and the virtual nature of the painted image; its formal synthesis blends 2D with 3D, painting with sculpture, representation with reality. The canvas gains or loses weight together with the fictitious gravity of the object contained within it.

(…) my working method has more often than not involved the subtraction of weight. I have tried to remove weight, sometimes from people, sometimes from heavenly bodies, sometimes from cities; above all I have tried to remove weight from the structure of stories and from language.

(Italo Calvino, American Lessons)

Our approach to the world passes through the surface of things: we see through the lens of wrapping and packaging.

Firstly, we are consumers of signs before contents. Visual culture – advertising, graphics, communication – has been seduced by the image and the same has happened with art. A painting which looks at the surface doesn’t have to be superficial and, if it is, the meaning doesn’t need to be negative.

Alessandro Baricco has recently written an article for the fortunate series of the New Barbarians, in which he imagines how the aesthetics of the future will be. A text used as stimulus by the curator of the Italian Pavilion at the 2010 Architecture Biennial, which tackles the problem of superficiality. One of the traumas caused by mutation – he writes – is finding ourselves living in a world which lacks a dimension that we had gotten used to, that of depth. I remember a time when more forward thinking minds had interpreted this curious condition as a symptom of decadence: not incorrectly, they registered the sudden disappearance of about half of the world they knew. What’s more, this was the half that really mattered, that contained the treasure. So ensued the instinctive inclination to interpret events in an apocalyptic way: the invasion of a Barbarian hoard which, lacking the concept of depth, was rearranging the world in the only remaining dimension it could, superficiality. With consequent disastrous dispersion of sense, beauty and meaning - of life. This wasn’t a stupid way of reading things, but now we know to a certain extent of precision that it was a short-sighted way: it swapped the abolition of depth for the abolition of sense. Baricco leads us to become aware: condemnation to superficiality is immoral and anachronistic; we run in the world of appearances, we feed and reproduce in the light of the images that represent us. The surface is the first point of contact, the interface with the world.

Marica Fasoli is a daughter of the Nineties, not just of a society focused on entertainment and consumerism, but of an era which has inexorably deviated its imagery, materialising the superficiality of the object, whatever it may be, making it available to everyone. Like many artists, from the late Fifties to the present day (just think of the noble packaging of Tom Sachs and the graphic effect of Antonio De Pascale’s painting), Fasoli has fallen in love with packaging, with the power connected with her pseudo-packages, just another trick to play with the fictitious nature of appearances. Superficiality doesn’t mean lightness, and lightness doesn’t mean absence of content. The projections of our desires deposit on the surface; the surface is the wrapping that separates what we are from what we can decide to be. More than desirable packaging addresses our expectations.

Fasoli’s half-open packaging is the intersection of several needs, those of consumers greedy for painting (in search of technical unveiling), of the society of appearances and of a human need for reality (or, better yet, for content). In her paintings, hyperrealism opens up to unprecedented forms of conceptualisation. Her paintings don’t hide but reveal mimetic deceit. Content and surface blending together.

Anyway, “handle with care”: the encounter with painting is unusual and doesn’t guarantee the security of what we think we recognise.